Table of Contents

Introduction

Have you ever considered what it actually means to have wealth? Usually when we say someone is wealthy, we mean that they have a lot of money. But wealth is a lot more than that. Wealth is defined more broadly as “the social worth of an economy’s entire productive base [which] consists of the entire range of factors that determine intergenerational well-being.” (Arrow, et. al., 2010)

Models of wealth creation often include many more attributes than just financial. For example, in their book Rural Communities: Legacy and Change, Flora and Flora (2004) promote the Community Capitals Framework (CCF) that includes the following types of wealth or capital:

- Built capital, this is the community’s infrastructure including roads, internet and telecommunications, water and sewer systems and others

- Cultural capital, the mixing of individuals from different cultures and the expression of their cultures through festivals or other events

- Financial capital, the money that individuals and organizations have themselves and have available for investment in new businesses

- Human capital, the knowledge, skills and ability of the individuals in the town

- Natural capital, the physical environment including lakes and forests

- Political capital, the connections between individuals and organizations with political forces, locally and regionally, in order to influence activities in their community

- Social capital, the connections between the individuals and organizations in the town

A rural wealth development strategy needs to take all of these things into account. While this can seem like a significant challenge, there are often many assets that can be leveraged in the process. Modern rural wealth development theories begin with taking inventory of the community’s assets, so-called Asset Based Community Development (ABCD, Collaborative for Neighborhood Transformation, n.d.)

ABCD builds on the assets that are already found in the community and mobilizes individuals, associations, and institutions to come together to build on their assets– not concentrate on their needs. An extensive period of time is spent in identifying the assets of individuals, associations, and then institutions before they are mobilized to work together to build on the identified assets of all involved. Then the identified assets from an individual are matched with people or groups who have an interest or need in that asset. The key is to begin to use what is already in the community.

A community development of the past may have looked at weaknesses and tried to rectify those. For example, individuals in a community may have a low level of education, have a lot of debt or financial pressures or even be lacking in basic needs such or housing. These are absolutely huge barriers to building wealth and should be addressed, but at the same time we can appreciate their assets:

- Community members are creative at finding ways to make “ends meet”

- There are likely empty lots or unused business spaces that could be revitalized

- Low levels of education mean that even small investments will have a large payoff

This is similar when we look at communities and organizations. A community may lack jobs, lack infrastructure or be unprepared to implement community development efforts. At the same time, they probably have a very good sense of what needs to change in their community – and that knowledge is golden.

Understanding the Bigger Picture

It’s important that any community development efforts start with a detailed picture of the situation. Community visioning or strategic planning may be helpful for this.

In a strategic planning session, you’ll invite community members, staff, and city/town council to contribute their views on what is working in the community and what would they like to be different. By involving members who live in the community you benefit from their experiences and knowledge. Additionally, when town residents have truly been included you see increased buy-in.

You may also develop a logic model or theory of change, that helps show how changes in your community will flow through to other stakeholders. For example, if you have the opportunity to build a hospital in an under-served community you’ll certainly benefit from the employment prospects of that facility but also you’ll see the health outcomes of that community change radically for the better.

On a smaller scale, if you can install some benches or other seating down-town near storefronts, you may see increased pedestrian traffic or conversation among people who previously would not have congregated in the area – improving the social capital of your town.

Wealth Indicators

In planning out community development interventions, it’s helpful to have wealth indicators that you can refer to. These are measures of specific types of wealth that can help you see noticeable change in the community. That will tell you your intervention is working, or that you need to tweak it in order to improve things.

Pender, Marré, and Reeder (2012) in their report Rural Wealth Creation: Concepts, Strategies, and Measures provide a comprehensive appendix of indicators. For example, one of the metrics they identify under physical capital is access to broadband internet. In order to measure the “% of population with access by number of providers, technology (DSL, fiber, cable, wireless), and speed ranges” suggest using the National Broadband Map which provides data by “County, Census places, [and] Congressional Districts.”

By selecting the metrics that are most important to you and then engaging in data collection after your visioning, you’ll be able to build a rural wealth creation plan that recognizes where your community is now and where they need to go.

While not strictly a Wealth Indicator, another useful form of data is the Location Quotient (LQ). The LQ tells you the employment rate of an industry in your area, relative to the the state or national rate (depending on the type of analysis you’re doing.) This helps you see what industries are more important in your area or bringing in more revenue and which are bringing in less.

If an industry is a large employer in your area, for example natural resource exploitation, your community will be more affected by changes in this area. That may compel you to diversify to lessen the impact of those changes. On the other hand, if an industry is less common (for example, professional services or tourism) you have a choice to make about whether you’d like to promote that industry in your area or whether you consider it too volatile.

Rural Development Strategies

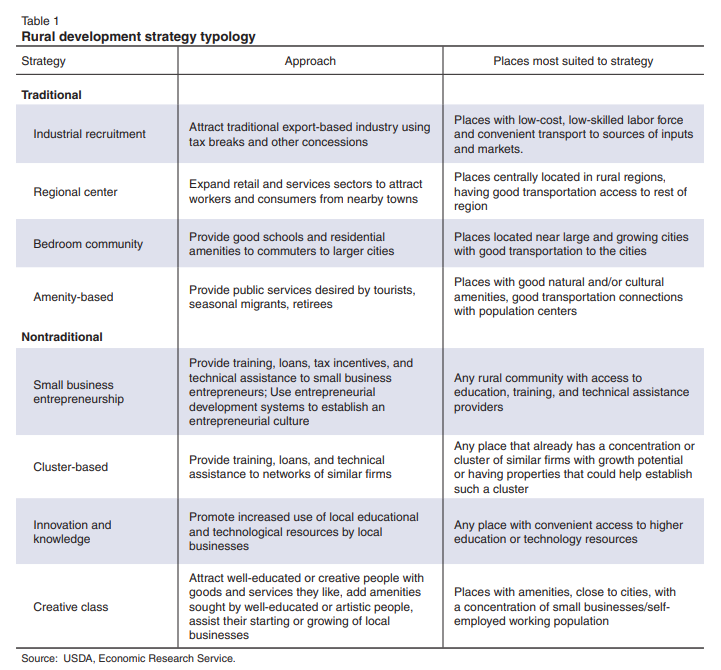

The report by Pender, Marré, and Reeder mentioned earlier includes a table discussing some strategies:

These can all be considered by communities interested in economic development. Your community probably already does some of these. Here are a few more that I think are under-utilized in rural and remote communities:

Working Remotely

In communities that have good internet access, working remotely is an option. There are lots of tech careers that permit working from home – which can allow wealth into the community with no associated polluting or commuting costs.

The major barrier to this strategy is ensuring residents have access to the technical skills they need to be successful working these jobs. There are, however, work-from-home jobs that require lower levels of education. For example, Sykes is a large employer of work-from-home workers. The salaries may be low ($10-12 an hour) but for someone on social assistance this is a large cash injection that may be helpful in paying off debts, paying bills and getting or staying on their feet.

Promote Not-for-Profits

There’s a focus on small-business entrepreneurship in deprived communities but there also exists a lack of nonprofits as well. A successful nonprofit can often have large ripple effects in a community.

For example, a nonprofit that decides to operate a food pantry or a crisis line and is able to achieve grant funding for their first year or two of operation will support the employee(s) of that venture but also support:

- Volunteers that gain new skills working with the nonprofit

- Recipients of the food or mental health aid that are more able to cope

- Other businesses that grant money flows to, for instance purchasing advertising or supplies

Financial Literacy

While not strictly a wealth-creation activity, improved financial literacy can help individuals get out of debt and stay there. High bills can be caused by unavoidable medical expenses or other bills that are out of a person’s control, but may also be caused by a lack of financial literacy.

Teaching individuals how to manage their bills, build credit responsibly and save to invest in higher education or retirement (for example) can ripple through a community as they have more access to disposable income over time. That disposable income may then be spent at merchants in the community.

Workforce and Higher Education Development

Gibson (2019) notes that another major barrier for rural economic development is that students are not leaving with the skills they need to be successful in regional jobs. Part of this is that many small communities do not have higher education. When students do leave, they rarely come back.

By building more programs in high schools to teach vocational skills, students will find themselves more prepared for the types of jobs available at that local and regional levels. They can begin earning an income and supporting local industry before they complete post-secondary education – especially if this education is available online.

Conclusion

Rural wealth creation is no easy task. It takes the investment and involvement of a dedicated portion of the community. Contrary to popular belief though, you do not have to be restricted just to attracting industrial jobs or other businesses to your community. Instead, you can support entrepreneurship, build the capacity of local community members and improve infrastructure in order to build wealth in your community.

References

Arrow, K.J., P. Dasgupta, L.H. Goulder, K.J. Mumford, & K. Oleson. (2010) Sustainability and the Measurement of Wealth. NBER Working Paper 16599. National Bureau of Economic Research

Collaborative for Neighborhood Transformation. (n.d.) “What is Asset Based Community Development (ABCD)”. Retrieved on Sep 1 2019 from https://resources.depaul.edu/abcd-institute/resources/Documents/WhatisAssetBasedCommunityDevelopment.pdf

Flora, C.B., & Flora, J.L. (2004). Rural Communities: Legacy and Change. 2nd Ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Gibson, J. P. (2019). accelerating american RURAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT. Economic Development Journal, 18(1), 40–45.

Pender, J., Marré, A. & Reeder, R. (2012) Rural Wealth Creation: Concepts, Strategies, and Measures. Economic Research Report Number 131. Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

1 thought on “Wealth Creation in Rural Communities”