Table of Contents

Introduction to Text and Chat

With text and chat services increasingly moving online, emotional support work – the core element of the work of crisis lines is needing to be adapted to work in new formats that require a change in your perspective and technique. On the telephone, there are a number of ways of providing a warm, genuine experience. For instance, your voice tone and pitch communicates a lot, as well as the speed in which you talk, whether you speak over the caller or let them lead, and so on. There is a lot of non-verbal communication that happens on the phone.

In contrast, online all you have is text. So many of the dimensions that are used to promote warmth, communicate empathy and demonstrate caring are simply absent. This makes it more difficult to build rapport with these visitors and be effective.

The elements of active listening, or the active listening process are the same, although of course it seems unusual to call it “listening” since you aren’t using your ears. There is still an effort made to be alert for and respond to communication, however. Some people prefer “emotional support” instead.

Chat and Text Length

Chat and text conversations tend to be longer than telephone conversations; an average telephone call may be 20 minutes while a crisis chat or text conversation will be 45-60 minutes. This is due to the time required for you to send a text, for the visitor to receive it, read it, decide what they’re going to write, and then write back. You may not send a lot of messages in this 60 minutes, but that doesn’t mean that you aren’t accomplishing a lot – which is reflected in the outcomes, often up to 30% reduction in subjective distress over an hour.

Opening Conversations

In the opening of a text-based conversation, it’s important to be warm and genuine. Your opening message should give your name, because the visitor doesn’t have anything else to go on. You may want or need to identify your organization as well. Finally, you’ll want to ask the visitor what brought them to text in.

An example of an opening message I could use on the ONTX Project is “Welcome to the ONTX Project. My name is Dustin, what’s going on in your life?”

Sometimes a visitor will text in with a lethality statement, something like, “I want to die.” This doesn’t necessarily change your opening, but it doesn’t hurt to acknowledge the suicidal feeling. “Welcome to the ONTX Project. My name is Dustin, it sounds like you’re really struggling. Did you want to tell me what’s been going on?”

Some visitors though, may need a bit of encouragement. If you ask a visitor how they’re feeling, they may reply “idk” (I don’t know) or “bad”, and not elaborate. Other visitors may be much more articulate and be able to explain what’s going on in their life.

If someone says “idk” or “bad”, usually my next move is to ask them what’s on their mind tonight. This is a gentle way of rewording the question that helps them feel more comfortable. Usually at this point they’ll begin talking, but if not my final option is “What were you hoping to get out of texting in tonight?”

I’ve never had a visitor respond with “idk” or other messages after this much encouragement but I would likely empathize with how difficult it’s been for them to text in before ending the conversation and inviting them to try us again when they’re more able to speak.

Because of a 140 character limit, some of these messages may need to be sent as a pair of messages on text.

Exploring the Issue

Exploring the issue that the visitor is texting in about can be challenging. Unlike the helpline, where you may need to take a while to establish rapport, visitors on text tend to jump right to their primary concern rather quickly. They don’t have the luxury of many messages back and forth.

If you’ve used the above Opening the Conversation ideas, you should be well into exploring the issue. This section should proceed just the same way as an offline conversation does, using all elements of the active listening process (open ended questions, paraphrasing and summarizing.)

You may notice that you need to ask more clarifying questions than usual, because with text and a lack of tone it’s easier for things to be misunderstood or misconstrued.

Demonstrating Empathy

In an online environment, you have no voice tone to demonstrate empathy. For this reason it’s important to write out your empathy statements clearly in order to show that you have an idea what the visitor is going through. Clarifying and paraphrasing can help in rapport building as well, by demonstrating that you are paying attention. It’s important to recognize that clarifying, paraphrasing and other open and close-ended questions are not a replacement for pure empathy.

Empathy: You sound really alone.

Clarifying: You just lost your dog?

Paraphrasing: You’ve been having trouble since you lost your pet.

Note the difference, empathy highlights an emotion (alone) while clarifying and paraphrasing primarily on content without regard to an emotional undertone.

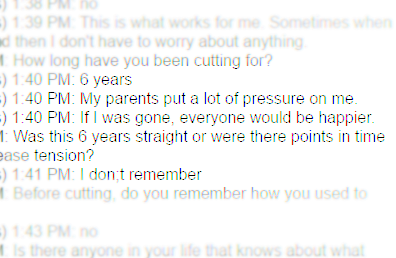

Suicide Risk Assessment and Intervention

Suicide risk assessment and intervention is a challenging topic over chat and text. The primary challenges in this environment include the difficulty collecting the amount of information required to perform a competent assessment in 140 characters and the lack of voice tone and body language.

Typically the first question asked on chat and text after confirming suicide thoughts are present is to determine if they’re at imminent risk. This is usually accomplished by asking something like “Have you done anything to kill yourself?” or “Have you taken any steps to end your life tonight?”

Chatters and texters will sometimes text in immediately after an overdose, and will readily reveal their level of danger but not until you ask. Sooner rather than later!

Next, I’ll ask the visitor what’s led them to feeling suicidal. This, when combined with an empathy statements, helps to begin exploring the visitor’s reasons for living or dying. For example, “You must be feeling so overwhelmed. Tell me what’s led you to feeling suicidal?”

After this, I move onto the elements of the DCIB Suicide Risk Assessment tool.

Winding Up Conversations

Because visitors are using their cell phones, they can put their phone in their pocket, and then pull it out without thinking about the time that passes in a few minutes. It’s not uncommon that at the end of your 45-60 minutes, when it comes to winding up, the visitor doesn’t even realize that amount of time has passed. They find themselves feeling better, however, which is great news!

Winding up has to be deliberate, otherwise the visitor is unlikely to wind up in a decent time. Past experience has shown that crisis chats can last 3 hours or longer lacking a proper wind up. In order to initiate a windup, you simply have to give the visitor an opportunity to express anything else on their mind and then let them know that you have to go. For example,

“We’ve been talking for about an hour so we’ll need to wrap our conversation up soon. I’m wondering if there’s anything else on your mind that you haven’t shared yet.”

Or, more succinctly,

“We’re just coming up on 45 minutes of chatting so we’ll need to wind up soon. Was there anything else you wanted to share before we do?”

This cues the visitor that the conversation needs to end and lets them focus on any outstanding issues. For instance, you may be convinced of their safety and they may not be – and by pointing that out by replying “I don’t know what to do to avoid attempting suicide tonight” then you can spend your remaining 15 minutes implementing a comprehensive safety plan for that visitor. In this way, the windup can be a tool for you and the visitor.